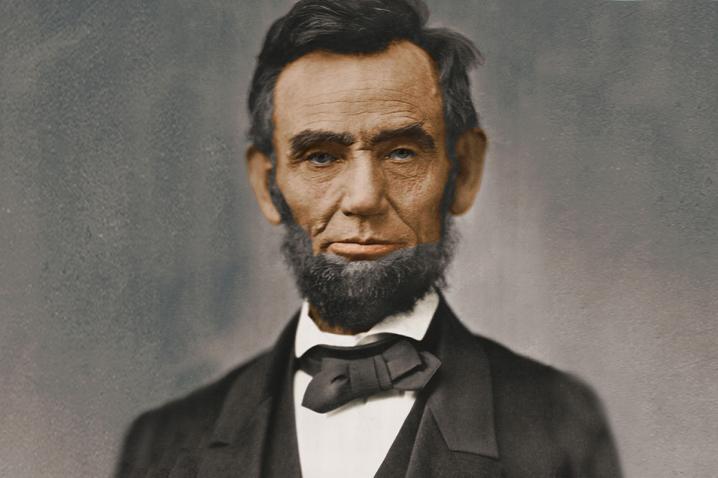

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln, sixteenth President of the United States, was born near Hodgenville, Kentucky on February 12, 1809. His family moved to Indiana when he was seven and he grew up on the edge of the frontier. He had very little formal education, but read voraciously when not working on his father’s farm. A childhood friend later recalled Lincoln’s “manic” intellect, and the sight of him red-eyed and tousle-haired as he pored over books late into the night. In 1828, at the age of nineteen, he accompanied a produce-laden flatboat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, Louisiana—his first visit to a large city–and then walked back home. Two years later, trying to avoid health and finance troubles, Lincoln’s father moved the family moved to Illinois. After moving away from home, Lincoln co-owned a general store for several years before selling his stake and enlisting as a militia captain defending Illinois in the Black Hawk War of 1832. Black Hawk, a Sauk chief, believed he had been swindled by a recent land deal and sought to resettle his old holdings. Lincoln did not see direct combat during the short conflict, but the sight of corpse-strewn battlefields at Stillman’s Run and Kellogg’s Grove deeply affected him. As a captain, he developed a reputation for pragmatism and integrity. Once, faced with a rail fence during practice maneuvers and forgetting the parade-ground instructions to direct his men over it, he simply ordered them to fall out and reassemble on the other side a minute later. Another time, he stopped his men before they executed a wandering Native American as a spy. Stepping in front of their raised muskets, Lincoln is said to have challenged his men to combat for the terrified native’s life. His men stood down. After the war, he studied law and campaigned for a seat on the Illinois State Legislature. Although not elected in his first attempt, Lincoln persevered and won the position in 1834, serving as a Whig. Abraham Lincoln met Mary Todd in Springfield, Illinois where he was practicing as a lawyer. They were married in 1842 over her family’s objections and had four sons. Only one lived to adulthood. The deep melancholy that pervaded the Lincoln family, with occasional detours into outright madness, is in some ways sourced in their close relationship with death. Lincoln, a self-described “prairie lawyer,” focused on his all-embracing law practice in the early 1850s after one term in Congress from 1847 to 1849. He joined the new Republican party—and the ongoing argument over sectionalism—in 1856. A series of heated debates in 1858 with Stephen A. Douglas, the sponsor of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, over slavery and its place in the United States forged Lincoln into a prominent figure in national politics. Lincoln’s anti-slavery platform made him extremely unpopular with Southerners and his nomination for President in 1860 enraged them. On November 6, 1860, Lincoln won the presidential election without the support of a single Southern state. Talk of secession, bandied about since the 1830s, took on a serious new tone. The Civil War was not entirely caused by Lincoln’s election, but the election was one of the primary reasons the war broke out the following year. Lincoln’s decision to fight rather than to let the Southern states secede was not based on his feelings towards slavery. Rather, he felt it was his sacred duty as President of the United States to preserve the Union at all costs. His first inaugural address was an appeal to the rebellious states, seven of which had already seceded, to rejoin the nation. His first draft of the speech ended with an ominous message: “Shall it be peace, or the sword?” The Civil War began with the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861. Fort Sumter, situated in the Charleston Harbour, was a Union outpost in the newly seceded Confederate territory. Lincoln, learning that the Fort was running low on food, sent supplies to reinforce the soldiers there. The Southern navy repulsed the supply convoy. After this repulse, the Southern navy fired the first shot of the war at Fort Sumter and the Federal defenders surrendered after a 34-hour long battle. Throughout the war, Lincoln struggled to find capable generals for his armies. As commander-in-chief, he legally held the highest rank in the United States armed forces, and he diligently exercised his authority through strategic planning, weapons testing, and the promotion and demotion of officers. McDowell, Fremont, McClellan, Pope, McClellan again, Buell, Burnside, Rosecrans–all of these men and more withered under Lincoln’s watchful eye as they failed to bring him success on the battlefield. He did not issue his famous Emancipation Proclamation until January 1, 1863 after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam. The Emancipation Proclamation, which was legally based on the President’s right to seize the property of those in rebellion against the State, only freed slaves in Southern states where Lincoln’s forces had no control. Nevertheless, it changed the tenor of the war, making it, from the Northern point of view, a fight both to preserve the Union and to end slavery. In 1864, Lincoln ran again for President. After years of war, he feared he would not win. Only in the final months of the campaign did the exertions of Ulysses S. Grant, the quiet general now in command of all of the Union armies, begin to bear fruit. A string of heartening victories buoyed Lincoln’s ticket and contributed significantly to his re-election. In his second inauguration speech, March 4, 1865, he set the tone he intended to take when the war finally ended. His one goal, he said, was “lasting peace among ourselves.” He called for “malice towards none” and “charity for all.” The war ended only a month later.The Lincoln administration did more than just manage the Civil War, although its reverberations could still be felt in a number of policies. The Revenue Act of 1862 established the United States’ first income tax, largely to pay the costs of total war. The Morrill Act of 1862 established the basis of the state university system in this country, while the Homestead Act, also passed in 1862, encouraged settlement of the West by offering 160 acres of free land to settlers. Lincoln also created the Department of Agriculture and formally instituted the Thanksgiving holiday. Internationally, he navigated the “Trent Affair,” a diplomatic crisis regarding the seizure of a British ship carrying Confederate envoys, in such a way as to quell the saber-rattling overtures coming from Britain as well as the United States. In another spill-over from the war, Lincoln restricted the civil liberties of due process and freedom of the press. On April 14, 1865, while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., Abraham Lincoln was shot by Confederate sympathizer, John Wilkes Booth. The assassination was part of a larger plot to eliminate the Northern government that also left Secretary of State William Seward grievously injured. Lincoln died the following day, and with him the hope of reconstructing the nation without bitterness.

Source: battlefields.org